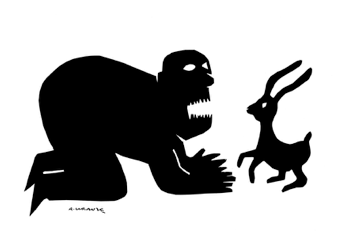

Andrzej Krauze describes himself as a visual clerk. ‘Everyday for the past forty years’, he would tell visitors and friends, ‘I go to my office, and I make two or three drawings. By now I’ve made 20 to 25,000. They are in these drawers. They are my babies. I can never find the one I am looking for, I am a very bad parent.’ He is proud to have angered those who despise him. Prime ministers and Presidents have demanded his sacking.

When I was researching an exhibition to mark the twentieth anniversary of the fall of the Soviet Union, I asked Andrzej Klimowski to recommend artists. Without hesitation he replied, ‘you must go to see Andrzej Krauze. When we were students he was our inspiration, and he still is today’. In the winter of 1981, when Martial Law was declared in his native Poland, Krauze was visiting the West. Already an established anti-establishment figure at home, the visual clerk pilloried those responsible with his paper and pen. His drawings flew around the world, and consequently Andrzej could not return home. He settled in England, and continued to draw.

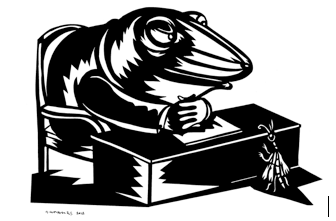

One of his best-loved characters is an anthropomorphic pen, similar to the one which Andrzej uses to draw. It is a mapping pen, the sort you dip in ink. Mr. Pen has suffered many indignities. He is an intellectual, an outcast, a questioner, a man much put-upon, a clerk with revenge in his heart- and a man who has quietly amassed many thousands of drawings.

Last year I began to work with Andrzej, we planned a series of etchings. He was excited at the thought of drawing with a nail. Then, suddenly, the project was put on hold. Andrzej needed to undergo serious heart surgery. On recovery he discovered that he was no longer able to draw.’ I have ideas’, he explained to me, tapping his forehead. ‘I have editors ringing everyday with commissions’ and then, as Andrzej does when he knows that a gesture can say so much more than a word, he shrugs – with his arms, his forehead, his lips and his eyes, and relaxing he simply states: ‘It is hopeless’. Over the coming weeks Andrzej visited me regularly, and we talked about his unemployment and absent muse. What might have happened in the operation? ‘They stopped by heart for five hours’, he explained ‘I was run by a machine, and when they put me back together, they must have left out something, you know the thing that makes you draw. They must have left it on the table.’

One morning, Andrzej turned up with a smile, and we retired once more for coffee. ‘The other day’, he told me, ‘I bought some flowers, and they came wrapped in black paper. He grew more animated with each word. ‘And then I just picked up some scissors and made these’, as he spoke Andrzej pulled a small collection of paper-cut images from a folder. They were funny. They were bitter. When we returned to londonprintstudio, I handed Andrzej a surgical scalpel, ‘this’ I said, hoping for maximum dramatic impact, ‘killed Mr. Pen, I think you should take it and seek revenge’. Over the coming weeks, Andrzej returned, each time carrying paper-cut images of increasing sophistication. One year after Andrzej’s operation, we co-published a small collection of these wonderful images.

John Phillips