Rorke’s Drift is a battle site of great importance. Located in Zulu Natal, it is also significant for South African printmaking.

In 1948 the National Party gained control of the British Colony of South Africa and established a state

based on racist ideas - apartheid. In March 1960 56 people were killed and 200 injured at the Sharpsville ‘Massacre’ in which the South African police opened fire on an anti apartheid demonstration. This event galvanized international public opinion against the regime.

One of many ad-hoc responses was the setting up of The Swedish Committee for the Advancement of African Arts and Crafts in 1961.The group raised funds to establish a trade link with black communities in KwaZulu-Natal. To develop this project the two young artists were appointed, Ulla and Peder Gowenius. The newly-married couple were graduates of the Konstfackskonan, Stockholm, Sweden’s leading art school, whose curriculum followed Bauhaus principles of integration between the arts, crafts and society. Ulla’s specialisms were textiles and weaving, Peder’s sculpture, printmaking and art education.

The Committee had links with the Lutheran missionaries at Rorke’s Drift, which was where the Gowenius’s arrived in September 1961, to research craft practices in the district. They found that traditional crafts were in decline and a divisive education programme, the ‘Native Craft Policy’ was a

mechanism for isolating the black population from Western culture.

In early 1962, the couple began to work with hospital patients recovering from tuberculosis, who had no activities to keep them occupied. Their aim was to provide craft-based training, which could be

economically useful once the patients returned home. Ulla began sewing, strip weaving and spinning in the women’s wards; Peder tried a number of initiatives, including watercolour painting in the men’s wards, but with little success.

His diary entry for 23 January records a conversation with a young man named Azaria Mbatha. “I have been on my bedfor six months. One is thinking too much. Help to give me something not to think.” Peder taught Mbatha the principles of lino-printing, which the young man took up with enthusiasm, producing on average a new print everyday. Muziweyixhwala Tabere, the patient in the adjacent bed also began to make prints. Within a few months the project had gained momentum. Patients were paid for their work, which was sold through mission circles, and at the end of the year an exhibition was organised at the Konstfackskonan in Stockholm.

The idea to expand the programme, and establish a training centre for occupational therapists to work

in other hospitals came from Allina Ndebele, the trainee nurse assigned to the Gowenius’s as translator. By 1963, this project had become the Evangelical Lutheran Church, (E.L.C.), Art and Craft Centre based at Rorke’s Drift. Over the next two decades, this small independent school made a significant contribution to training black artists under the apartheid system. Weaving workshops established alongside the art school provided the principal income through an annual exhibition in Stockholm, private commissions, sales to tourists visiting the battlefields and the mission community. In 1965 students at the Konstfackskonan raised funds to enable Mbatha to study with them in Sweden; Mbatha went on to become one of South Africa’s leading black artists.

The Gowenius’s, and many of the other teachers who worked there, were paid as missionaries, but played little or no part in religious affairs. A rich variety of printmaking activities were taught in the school. By 1966 seven qualified advisors had been placed in local hospitals, and weaving workshops were established in a number of other centres. The following year there were major commissions and in 1968 four tapestries were included in the South African exhibit at the Venice Biennale.

The style of work, for which the centre and the artists who trained there is most popularly known, is the black and white linocut tackling social themes and subverting religious imagery. Mbatha’s early print of a black David defeating a white Goliath is a typical example of a style that became closely associated with an art resisting apartheid.

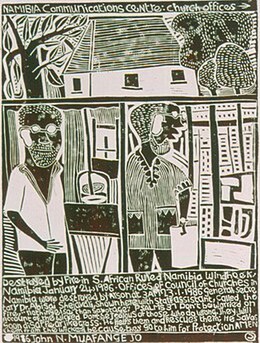

The most internationally recognised exponent of the style is John Muafangajo, who came from Namibia. In 1967 he was sent to study under Mbatha at Rorke’s Drift. In 1971, his application to study at the University of Cape Town was rejected. Ironically that same year he was selected as one of

three artists to represent South Africa at the Sao Paulo Biennale, were he received an award for the print, The Battle of Rorke’s Drift.

Muafanegjo’s most celebrated print Hope and Optimism in Spite of Present Difficulties, was the inspiration behind an international arts programme supported by UNESCO; the Hope and Optimism

Portfolio, which contains graphic works by over one hundred artists from around the world. Hope and Optimism in Spite of Present Difficulties also featured enlarged as the backdrop banner for the two Wembley concerts in 1988 and 1990, which celebrated the seventieth birthday of Nelson

Mandela, and the liberation of South Africa from the Apartheid regime.

John Muafangejo died on 27 November 1987, one month after his solo exhibition at the Royal Festival Hall in London. He had achieved an international reputation, a rare feat for any printmaker, an even rarer feat, at that time, for a black South African Artist. In his will he left provision for the training of ‘an artist from Namibia’. Muafangejo had always dreamed of creating an art school. In 1988, in

commemoration of the artist, a small group of activists set up a community arts project for children and young people in the Katatura district of Windhoek, Namibia’s capital city. Fuelled by volunteerism and supported by Unions and political parties, they ran regular workshops and events for the next four years. In 1992 this project, called The John Muafangejo Arts Centre, closed.

Two years later it reopened in centrally located premises offering classes in drawing, design, printmaking and illustration for artists and students During the Apartheid period, Katatura was the

location of a large fenced camp for 15,000 black South African workers. Not surprisingly, it was a centre of agitation and protest. The movement for the country’s independence grew from this base. In the 1980s the camp, and most of its buildings, was demolished, but one building, the kitchen, remained - a large, two-storey brick-and-concrete edifice.

In 2003, the Katatura Arts Centre opened in this building housing a theatre, pottery, radio station, fashion and design schools, a large computer suite and the print studio of the John Muafangajo Arts Centre. The equipment is basic, one etching press. Many of the artistsand students who use the facility make their prints in the traditional Asian manner, without a printing press. The images are cut from cardboard, using a reduction method, which frequently employs many coloured layers.

The cardboard matrix is peeled to different depths tocreate tone. The artists, whose aim is to make

printmaking the one art for which their county is famous,employ these principles and techniques with considerable ingenuity.

John Phillips, written 2005